What the Hair Remembers

— Reflections after Watching Nneka Kai's Lasting ’til Sunday

2025.11|by Echo Huan|Reflective Essay

A rhythmic shaking sound, sharp, steady, almost hypnotic, filled the far gallery of the Art Institute's On Loss and Absence exhibition on the morning of November 16, 2025. Nneka Kai's mother was shaking a container of beads, waiting for the moment her daughter would thread them into her hair. Then: a clatter. A single bead had escaped, hitting the wooden floor and breaking the rhythm.

I watched as Kai's mother pressed her lips together, her hands going still, her expression that of a child who has just made too much noise. The moment lasted only seconds, but it revealed the core of what I would witness over the next two hours: a reversal of care.

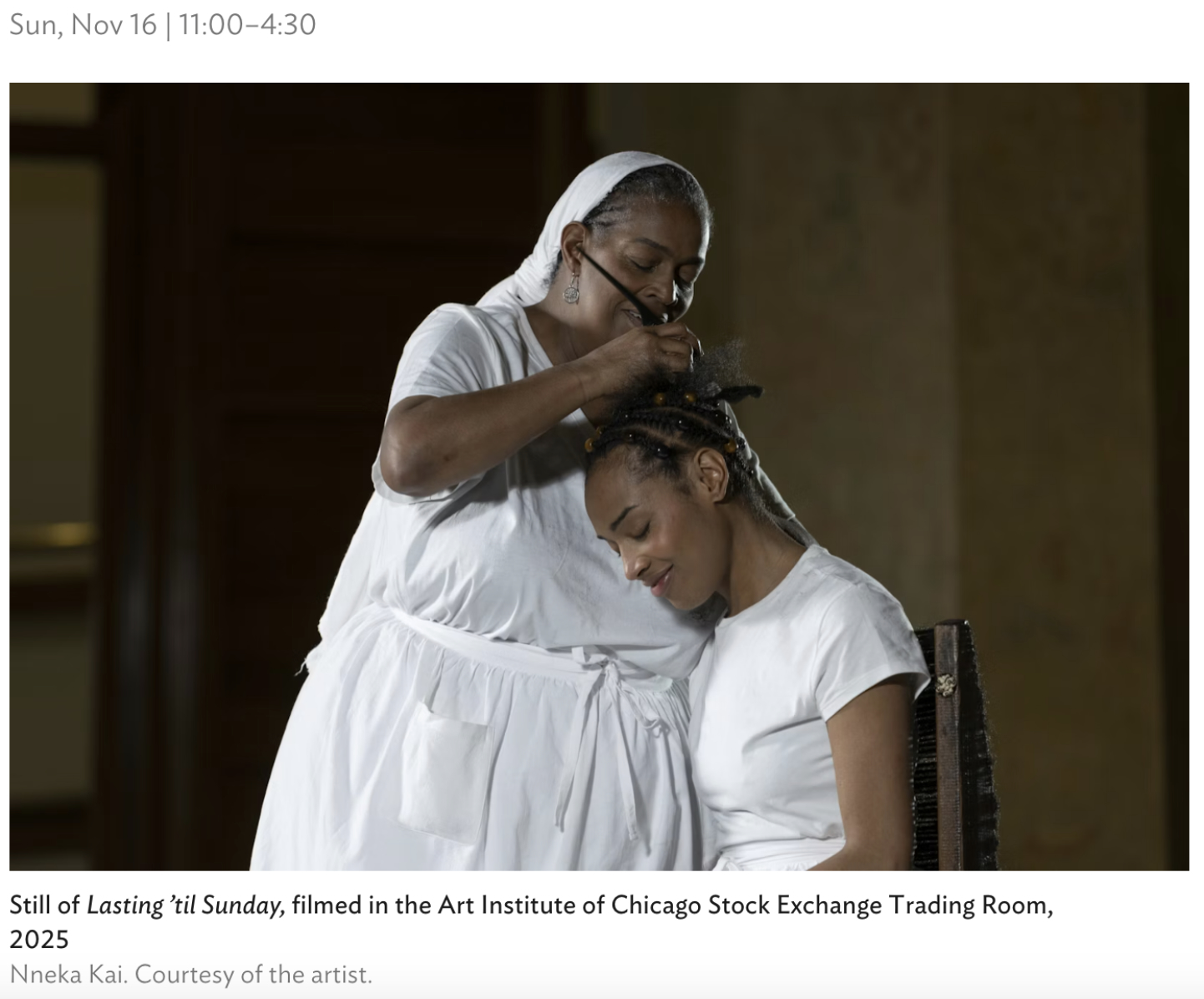

I had arrived just as the performance began at 11 a.m. and would stay for the full two hours. The spatial setup was itself a kind of mirroring: on the wall, a video from February showed Kai's mother braiding her daughter's hair in the Art Institute's Chicago Stock Exchange Trading Room. Now, in the gallery, Kai sat behind her mother in a chair she had handmade from hair, wood, and black-eyed peas, both of them facing that screen, their backs to us. As the video played — mother's hands moving through daughter's hair — the live performance unfolded in reverse: daughter's hands moving through mother's short hair, gathering, twisting, beading. Two moments in time, two braiding sessions, reflected back at each other like facing mirrors. Power, patience, control, everything had reversed, yet somehow remained the same.

But to understand what I was witnessing: this reversal, this ritual, this inheritance being passed backward and forward simultaneously. I first had to understand the material itself. I had to understand what hair does, what it carries, what it remembers.

"Hair gathers a person's thoughts as it grows. It accumulates them in the form of indeterminate particles, so that if you should want to forget something, or make a change or a new start, you should cut off your hair and bury it in the ground."

The Polish writer Olga Tokarczuk once wrote: "Hair gathers a person's thoughts as it grows. It accumulates them in the form of indeterminate particles, so that if you should want to forget something, or make a change or a new start, you should cut off your hair and bury it in the ground."

This passage comes to mind each time I think about hair. Tokarczuk frames hair as a living archive—not merely identity worn on the head, but memory made material. Hair expresses genetic inheritance in visible form: the degree of curl, the thickness of each strand, the texture soft or wiry. All of these are transmissions, inheritances carried forward through generations. And hair also holds what we have experienced, preserving the memories accumulated through time. What grows from us remembers for us.

Kai writes that her mother used these Sunday braiding sessions to teach her children about a material inheritance stretching across the Atlantic Ocean, connecting them to West Africa before the slave trade, where hair was a significant part of community, identity, and spirituality. As a single mother of three, Kai's mother dedicated every Sunday to caring for her children's hair. Through this ritual, she instilled what Kai now recognizes as "a method of survival and a source of pride, inscribing into her children's hair a language that could never be fully silenced."

Watching Kai braid her mother's hair, I found myself drawn to her own hair. Unlike a typical braid bound tightly to the scalp, hers consisted of a single long strand that ran from the left side of her head to the right, falling all the way to her ankles. Her hair seemed to become an extension of her emotional state. When she worked calmly, examining beads or moving steadily through a section, that long braid hung perfectly still. But when her hands grew tense or struggled to grip her mother's short hair, the braid swayed and trembled in response.

This movement kept drawing my attention to an object she had selected for the exhibition: a twentieth-century Bamiléké dance hat from the Art Institute's Arts of Africa collection. As co-curator of this exhibition, Kai had chosen objects that would reflect her performance. The hat features six long, cross-looped wool "braids" secured to a dome-shaped, woven-wood basket. In her research, Kai explains that this hat would traditionally have been worn by a masked dancer during secret ceremonies, acting as mediator between worldly and otherworldly realms. A cloth would have covered the wearer's face, bringing attention to the motion of the hat itself. She writes: "I could envision the braids swaying rhythmically during these performances, mirroring the dancer's gestures. I could sense that it was all about the braids."

Yet the hat has stiffened over time, potentially due to moisture, temperature, or lack of use. For Kai, this transformation illustrates how objects can be altered, both materially and conceptually, once they enter museum collections. The Bamiléké dance hat was not meant to be still and silent but rather to be activated through the wearer's performance. Now it sits motionless behind glass.

I kept thinking about another kind of constraint. Kai writes that since the Middle Passage, Black hair has been "literally subdued, crushed, and straightened to conform to dominant Eurocentric beauty standards." The wearing of natural Black textures and styles has therefore become "an act of resistance and a statement of freedom." Black hair is, in her words, "a unique material language, a signifier of the fight for liberation, carried upon one's head."

Is the museum's preservation of the dance hat not another kind of constraint? In prioritizing Western standards of conservation, has the institution sacrificed the hat's essential value: its capacity for movement, for freedom, for beauty in motion? Watching Kai's performance, I kept returning to this tension. Her swaying hair revealed a freedom within the contemporary art context. That movement made visible what might otherwise remain hidden: the tension, the calm, the embodied emotion extending outward for all of us to witness.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The chair Kai's mother sat in extended this archive beyond the body, beyond a single moment in time. Kai had handwoven it from hair, wood, and black-eyed peas—materials that, in her words, were "all part of this restorative space-making" during those childhood Sundays. The chair itself reflects the improvised nature of those early braiding sessions. As a child, Kai would sit wherever her mother found the best light: sometimes on a regular chair stacked with books to raise her height, sometimes on pillows laid out on the floor, sometimes on the couch. The setting changed, but the ritual remained constant.

Each material in this braiding chair carries memory. The hair woven into its seat and back is soft enough to feel warm, yet braiding transforms it into a remarkably strong textile—a paradox of vulnerability and resilience. The wood provides structure, the enduring frame, yet it is far from a simple support. Kai carved the chair from what appears to be a tree stump, using tools to hollow out the center portion inward, creating an hourglass shape that narrows where the body meets the seat. This carved indentation is not just for looks. It represents the passage of time, making labor tangible and visible in form. It also embodies a specific memory: the physical reality of those childhood braiding sessions. Sitting in that chair for hours was never truly comfortable. It was a form of rest, yes, but also a form of endurance. This discomfort was something both the braider and the one being braided had to bear together, part of the ritual's cost. And the black-eyed peas, visible when you look closely, speak to nourishment in multiple forms. Kai remembers the smell of her mother's cooking filling the house during those marathon braiding sessions: black-eyed peas simmering in a crockpot with turkey necks, cornbread, rice. "I can't help but think about nourishment," Kai said during the interview right after the next day of performance, "and a type of feeding." The chair offers rest to her mother. "Black women deserve to have a little break," she said, but it also offers something deeper: the chance to reverse care, to give back what was given.

Creating this chair was, for Kai, an act of honoring. "It's an honor for me to braid your hair," she said to her mother during the interview. The chair becomes witness to this reversal, holding not just her mother's body but also the accumulated weight of all those Sunday afternoons—the conversations, the lessons, the survival encoded in each twist and braid. What began as personal inheritance becomes, through the chair's presence in the museum, a communal archive. Everyone watching became part of what the chair was holding.

The spatial arrangement of the performance was itself a study in reversal. In the video playing on the wall, filmed in February 2024, Kai's mother braided her daughter's hair while facing the camera, facing us, the audience. Now, in November's live performance, Kai sat behind her mother braiding her hair, but both of them faced the video screen, their backs to us. It created a strange doubling effect, like looking into facing mirrors. As we watched the live performance unfold, we simultaneously witnessed its inverse: the video of what had come before, the last time the care had flowed in the original direction.

The facial expressions mirrored each other perfectly, as if the roles had simply been swapped and replayed. In the video, Kai's mother worked with a serious, concentrated expression while Kai sat calmly, eyes closed, occasionally smiling, waiting and receiving. In the live performance, those expressions had transferred: now Kai wore the look of serious concentration while her mother sat with eyes closed, smiling peacefully, receiving care.

This video documented the last time Kai's mother would braid her daughter's hair. Due to health conditions, her mother's hands could no longer perform the sustained, intricate work that braiding demands. The video had become a record of an ending. This knowledge gave weight to everything I was watching. The reversal was not simply an artistic choice or a symbolic gesture. It was a necessity, reality, the inevitable progression of care across a lifetime.

Braiding has always involved a particular form of control. As children getting our hair braided, we knew this well -- the moment when our mother pulled too hard, when the comb caught and tugged at the scalp, when we wanted desperately to escape but were told firmly to sit still, to endure, that it would be over soon. This is a universal mother-daughter image, transcending culture and geography. The mother has all the power. She's controlling your body, telling you to sit still, and you just have to wait it out. The child must endure, must trust that the discomfort serves a purpose.

Now the daughter held that power. Braiding requires constant assessment of the overall design, the pattern's direction, and its balance. I watched as Kai placed both hands on her mother's head, gently but firmly turning it left, then right, tilting it forward or back to check her work and determine her next move. Her mother's head became subject to her daughter's hands, adjusting and readjusting to facilitate the braiding process. The one who had once said "sit still" now had to sit still herself. The one who had once controlled another's body through touch now had her own body guided, positioned, held in place by another's judgment and need. The power had shifted, though both remained bound by the same ritual.

Yet the most striking moment of reversal came unexpectedly, in the incident I described at the beginning of this essay. Throughout the performance, Kai's mother held a container filled with beads, shaking it rhythmically. The sound had become part of the performance's texture, a gentle percussion marking time. She seemed to want to participate, to contribute something beyond simply sitting still. But then she shook too strongly. Beads jumped out from the container and scattered across the wooden floor, their clatter breaking the gallery's quiet. Immediately, her hands froze. She pressed her lips together and stopped shaking, her expression exactly that of a child who has just made too much noise, who has disrupted something important, and knows it. In that instant, the roles completed their reversal. The mother who had spent decades as the authority, the one in control, had become the child. The daughter who had once been corrected and guided had become the one holding space, the one in charge.

Both women performed barefoot, and before allowing her mother to stand at the performance's end, Kai crouched down and carefully picked up every scattered bead, ensuring her mother would not step on them. It was such a small gesture, so easily missed, yet it contained everything.

Throughout the two hours, I noticed other moments of tenderness woven into the control. Kai would occasionally stretch her own body, rolling her shoulders or flexing her hands. Her mother, as part of the performance, sat as still as possible, not daring to move. In these moments, Kai would reach out and squeeze her mother's shoulder, lean in to whisper something in her ear, or gently hold her mother's arms and elbows, which had grown tense from holding the bead container for so long without relief. These gestures said: Thank you for sitting still for me.

Control and care are not opposites but co-exist. The daughter's hands guiding her mother's head were both directive and tender. The firmness was necessary for the work, but it was never harsh. What I witnessed was not only a simple role reversal but also a deepening, a maturation of the relationship. The daughter had learned something beyond technique. She'd learned how her mother did it: holding someone still, but with love.

While watching the performance, around me, other viewers had settled into watching, and observing them became its own form of witnessing.

A mother and son had been there from the beginning. The boy, wearing a cowboy hat, lay on his stomach on the floor, watching the performance while drawing on his own paper. His mother leaned close, narrating quietly: "See, now she's threading the beads. Now she's braiding." The boy seemed mesmerized, his pencil moving as his eyes stayed fixed on Kai's hands. In the interview the next day, Kai mentioned this moment. She had noticed him sketching and thought, "Oh, it is an extension. I don't have to do anything. The people watching actually become part of this narrative. They are experiencing it, representing it, or understanding it in their own way, whether that's drawing or whether that's having a dialogue."

Nearby sat a family of four: parents and two daughters. The younger girl watched with her mouth slightly open, completely still, utterly absorbed. After about five minutes, the father appeared restless and moved to pick up the girl from where she sat on the floor, ready to move on to other galleries. "No!" she said loudly, pulling back. "I want to stay." They stayed for over half an hour, a remarkable feat of attention for such young children. They were white, and I imagined they likely had never witnessed or experienced Black hair braiding in their own lives. Yet something in this performance held them.

During the interview, Kai told us about another moment that had moved her, one that occurred even before the live performance began. She had come into the gallery one day and saw a woman with her daughter and husband watching the video. The daughter sat down, and as Kai's mother's voice played from the screen, this visiting mother placed her hand on her own daughter's head and began stroking her hair. They did not speak. They did not need to.

"The feelings they felt were represented in that one moment," Kai said. "You see something, you don't necessarily do what you see, you appreciate it. But to know that it resonated with something physical, which is what I was looking for in the first place."

I came to this performance carrying my own memories. My grandmother braided what we call "scorpion braids" in Chinese tradition. The particular way her hands moved, the specific pressure that meant trust had been built over time. Watching Kai and her mother, I felt those memories reactivate, become present again. The performance invited this. It created space for each of us to recall our own inheritance of touch, our own experiences of care given and received through the body.

Nneka Kai feels like someone turning a page in history—bringing women’s braiding practices back into the historical record, insisting that they be seen and discussed. In the museum, we see a Bamiléké dance hat preserved from what appears to be a male ritual tradition, yet braiding—the kind performed by mothers every day—demands far more time, care, and lived experience. Fiber art has long questioned the boundary between craft and fine art. Is the act of braiding itself art? How should we regard the cultural traditions of specific communities within museum spaces? How should we understand the cultural meaning that lives in communities, in daily life? These are questions worth staying with. I don’t intend to provide a universal answer here, but I will continue to carry them into my own creative process.

I imagine that, over time, my memory of this piece may fade. But I am certain that one quiet Sunday morning, while combing or braiding my hair, I will remember it again—remember how deeply it moved me. Hair is a vessel; it helps us hold the love of those who have tended to us, day after day, strand by strand.

Bibliography

Tokarczuk, Olga. House of Day, House of Night. Translated by Antonia Lloyd‑Jones, Granta Books, 2002.

Facio, Isaac, et al. On Loss and Absence. 2025.

“Gallery Performance: Lasting 'Til Sunday | the Art Institute of Chicago.” The Art Institute of Chicago, 2025, www.artic.edu/events/6300/gallery-performance-lasting-til-sunday. Accessed 19 Nov. 2025.

Kai, Nneka. In- Gallery Conversation of "Lasting 'till Sunday". Interview by Leslie M Wilson, 18 Nov. 2025.